14 June 2024: Bach Museum and Archive

Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena Bach

After my lightening visit to the Grassi Museum of Musical Instruments I rushed to meet Cathy at the Bach Museum and Archive.

We had booked for a guided tour of a special exhibition titled Voices of Women from the Bach Family.

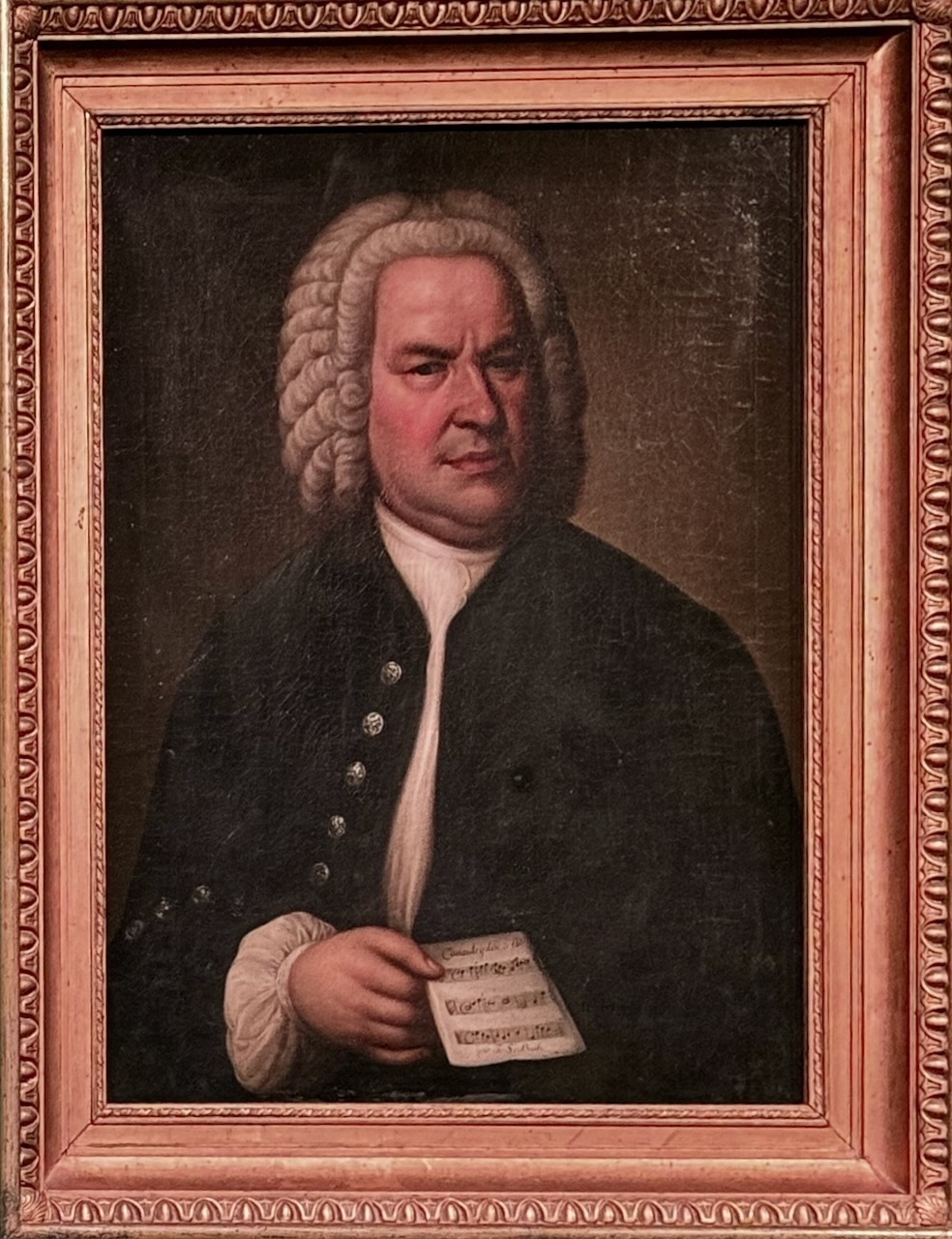

I was also keen to see the famous portrait of Johann Sebastian by Elias Gottlob Haussmann. This portrait is so iconic that you might even call it the Mona Lisa of Music.

The special exhibition was a fascinating tour de force.

The name Bach is associated with the composer Johann Sebastian Bach all over the world. But what is known about the women of the famous family of musicians?

I was inspired to look more deeply into the life of Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena, and her important and selfless contribution in support of her famous husband.

Bach Museum and Archive

This is a must see if you are in Leipzig.

The website is excellent and worth a look. It has lots of information and images.

It’s also worth giving the Virtual Museum Tour a go:

Virtual Museum tour with Google Arts & Culture

Voices of Women from the Bach Family

Voices of Women from the Bach Family

It’s impossible to do justice to this exhibition in a blog post, but here are some snippets from the website and wall texts. There was so much to look at and listen to.

The exhibition sheds light on their biographies and scope for action over a period of 200 years. At audio stations, the women of the Bach family themselves raise their voices and talk about their lives.

When Johann Sebastian Bach told a friend about his family’s musical talent, he highlighted two women in particular: his wife Anna Magdalena and his daughter Catharina Dorothea.

“… especially as my current wife sings a perfect soprano, and my eldest daughter isn’t bad either …” — Johann Sebastian Bach: Letter to Georg Erdmann, 28 October 1730

A man of few words.

What might have happened if society had granted women the same rights and opportunities as their male relatives? What professions might they have pursued? What music might they have composed?

Indeed.

Thanks to the research of musicologist Maria Hübner, we now recognise 33 women from the Bach family as distinct personalities.

She has meticulously compiled widely scattered information, analysed original sources, and thus outlined biographies of women from the 17th century to the 19th century.

This exhibition presents them in various roles: as family managers, singers, businesswomen, and members of communal living arrangements.

From Bach’s mother to his great-granddaughters, they find their voices in fictional stories. Portraits of European female musicians, stage artists, composers and poets from the Ton Koopman Collection further enrich our perspective.

A truly remarkable amount of research and some touching stories.

There were many images of female musicians

Women in Music

There had always been women involved in making music and composing, yet they rarely had the opportunity to develop their talents freely. They were obstructed by legal and social barriers. Historiography tended to ignore, undervalue, or entirely erase female musicians and composers.

The portraits show female stage artists, composers, poets and amateur musicians from Europe. Musical instruments, costumes, gestures, sheet music, clothing, interiors and inscriptions all reveal something of their activities and social status.

Portraits of deceased Protestant women from the 18th century depict them playing a hymn or holding a piece of music to highlight their piety and gentleness. In 19th-century women’s magazines, musical instruments were pictured as fashionable accessories.

Anna Magdalena Bach

Unfortunately there is no authentic surviving portrait of Anna Magdalena Bach (1701–1760), though we know one was painted.

What did Anna Magdalena Bach look like?

Anna Magdalena Bach, née Wilcke, was born in 1701 in Zeitz, Germany, into a family of musicians. Her father, Johann Caspar Wilcke, was a court trumpeter and her early exposure to music undoubtedly shaped her future as a talented soprano.

She secured a position as a singer at the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen (Cöthen), where she met Johann Sebastian Bach. He was the court kapellmeister from 1717–23. This is where he wrote the Brandenburg Concertos.

Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena married in 1721 after the death of Bach’s first wife, Maria Barbara. They moved to Leipzig in 1723 when Johann Sebastian was appointed cantor of St Thomas church.

Anna Magdalena played a significant role in Bach’s life and work. Not only was she a skilled musician, but she also became an integral part of Bach’s musical endeavours. She often copied Bach’s compositions, including some of his most important works, such as parts of the B Minor Mass and the solo cello suites.

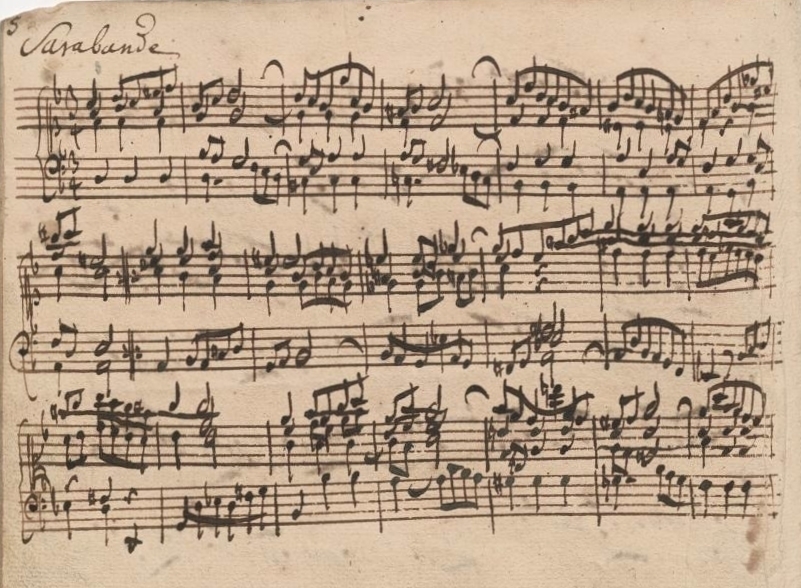

Sarabande from Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach (1722)

Copied by Anna Magdalena Bach

The couple had a large family. Anna Magdalena bore thirteen children, though many did not survive into adulthood. Despite the challenges of a large household, Anna Magdalena continued to contribute to Bach’s work. She would have contributed significantly to the musical education of her children, some of whom are still know as composers today: Johann Christoph Friedrich (the ‘Bückeburg Bach’) and Johann Christian (the ‘London Bach’).

As if she did not have enough on her plate, in 1749 Johann Sebastian’s health deteriorated. He suffered from a serious eye condition as well as motor problems in his right arm and his writing hand. In 1750 he underwent eye operations in March and April (by a charlatan it turns out) and he was able to see again for a short time, but then suffered a stroke and died on 28 July. He was only 65 years old; Anna Magdalena was 48.

After her husband’s death, Anna Magdalena’s life became increasingly difficult. Left without significant financial support, she spent her final years in poverty, dependent on charity and the assistance of her children and step-children. She was still responsible for her two youngest daughters, aged 8 and 12 years and her 26-year-old mentally handicapped son Gottfried Heinrich.

Anna Magdalena died in 1760, largely forgotten by the public.

David Yearsley’s book Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and Her Musical Notebooks provides an in-depth cultural and musical biography that sheds light on Anna Magdalena’s role within the Bach family and her significance in the broader context of 18th-century music.

After leaving her parents’ home to take up a court post as a professional singer, Anna Magdalena Bach née Wilcke (1701–60) would go on to become, through her marriage to the older Johann Sebastian Bach, a legendary musical wife and mother. … What emerges is a humane portrait of a musician who embraced the sensuality of song and the uplift of the keyboard, a sometimes ribald wife and oft-bereaved mother who used her cherished musical Notebooks for piety and play, humour and devotion – for living and for dying.

Book reveals life and times of Anna Magdalena Bach

Here are some more links I found interesting:

- Anna Magdalena Bach née Wilcke – Biography

- Anna Magdalena Bach (wikipedia)

- Johann Sebastian Bach – A chronology (Bach Archive)

- Johann Sebastian Bach (wikipedia)

- Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach (wikipedia)

- Bach Family (wikipedia)

The Bach Portraits

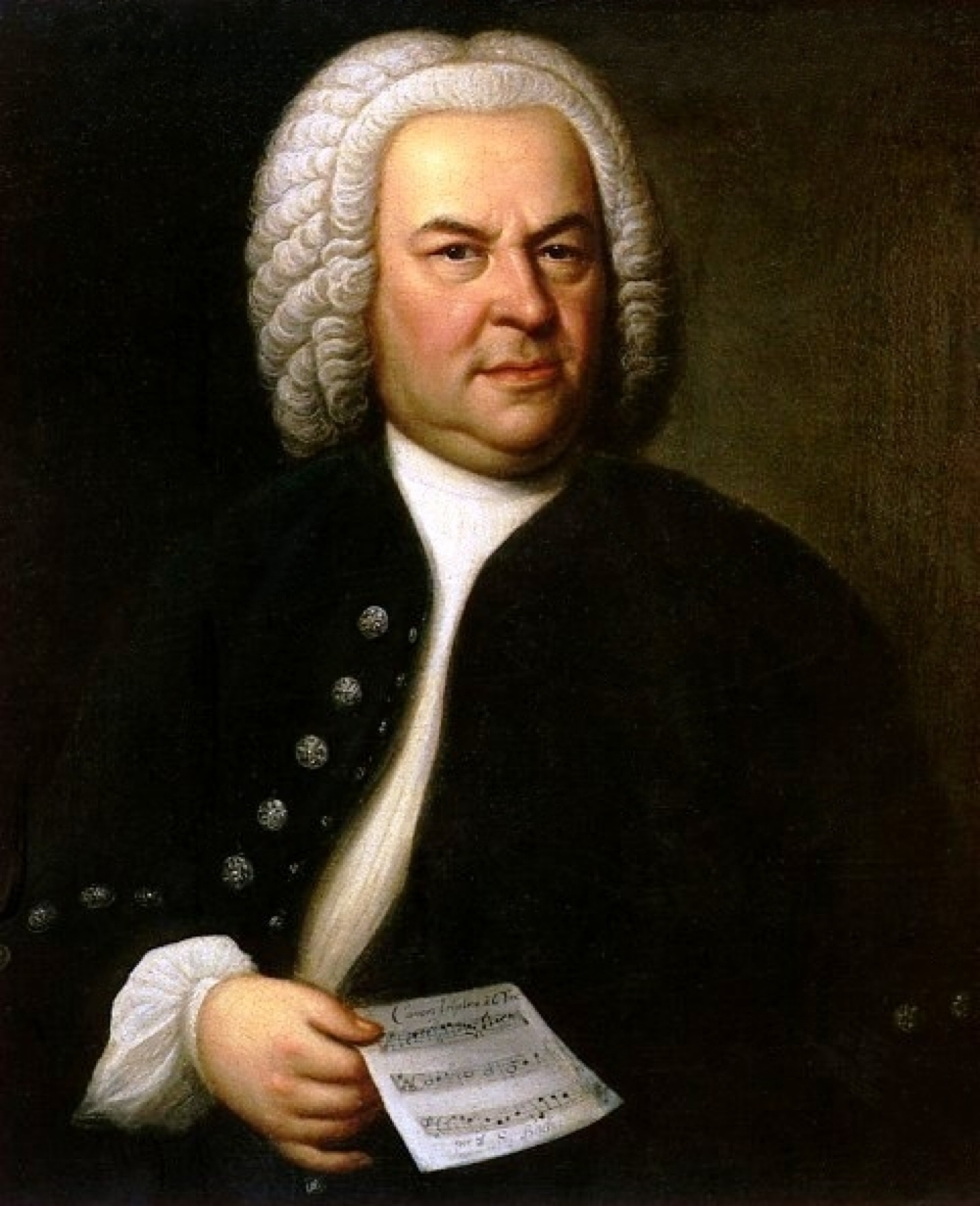

The Bach Museum’s permanent collection includes the Treasure Room (there was a similar room at the Grassi Museum). It houses one of the two iconic portraits of Johann Sebastian by Elias Gottlob Haussmann.

The Treasure Room

In the Treasure Room, the Bach Museum exhibits its most valuable items.

In the display case in the centre, you’ll find its most precious objects – original documents written in Johann Sebastian Bach’s own hand. His manuscripts and many of the other documents, music scores and prints are so fragile that they have to be changed over several times a year.

The 1748 portrait of Bach in the Treasure Room

The Mona Lisa of Music

The Correspondierende Societät der musicalischen Wissenschaften

In 1738 Lorenz Christophe Mizler (1711–1778) – a music theorist, publisher and philosopher – founded the Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences in Leipzig. The society’s goal was to elevate musical sciences by incorporating history, philosophy, mathematics, rhetoric, and poetry.

Its members were primarily composers, music theorists and mathematicians. Telemann joined in 1739 (the 6th member) and Handel in 1745 (the 11th member). Members were encouraged to contribute essays on music theory, history and practice. The society also published a journal.

A new member had to submit a written work on a musical or theoretical topic and also a portrait. According to rule 21 of the society:

each member should at his convenience send a picture of himself, well painted on canvas, to the library, where it will be retained as a memento and an etching of it used to illustrate the account of that member’s career when it is related in the annals of the Society.

Bach joined the society in 1747. He had delayed accepting his invitation until he could become the 14th member. The number 14 held a special significance for Bach because in numerology B-A-C-H adds up to 14 (B=2, A=1, C=3, H=8). This was a very Bach thing to do: he often used number symbolism in his compositions and personal decisions.

The Haussmann Portraits

Bach commissioned a portrait from Elias Gottlob Haussmann in 1746.

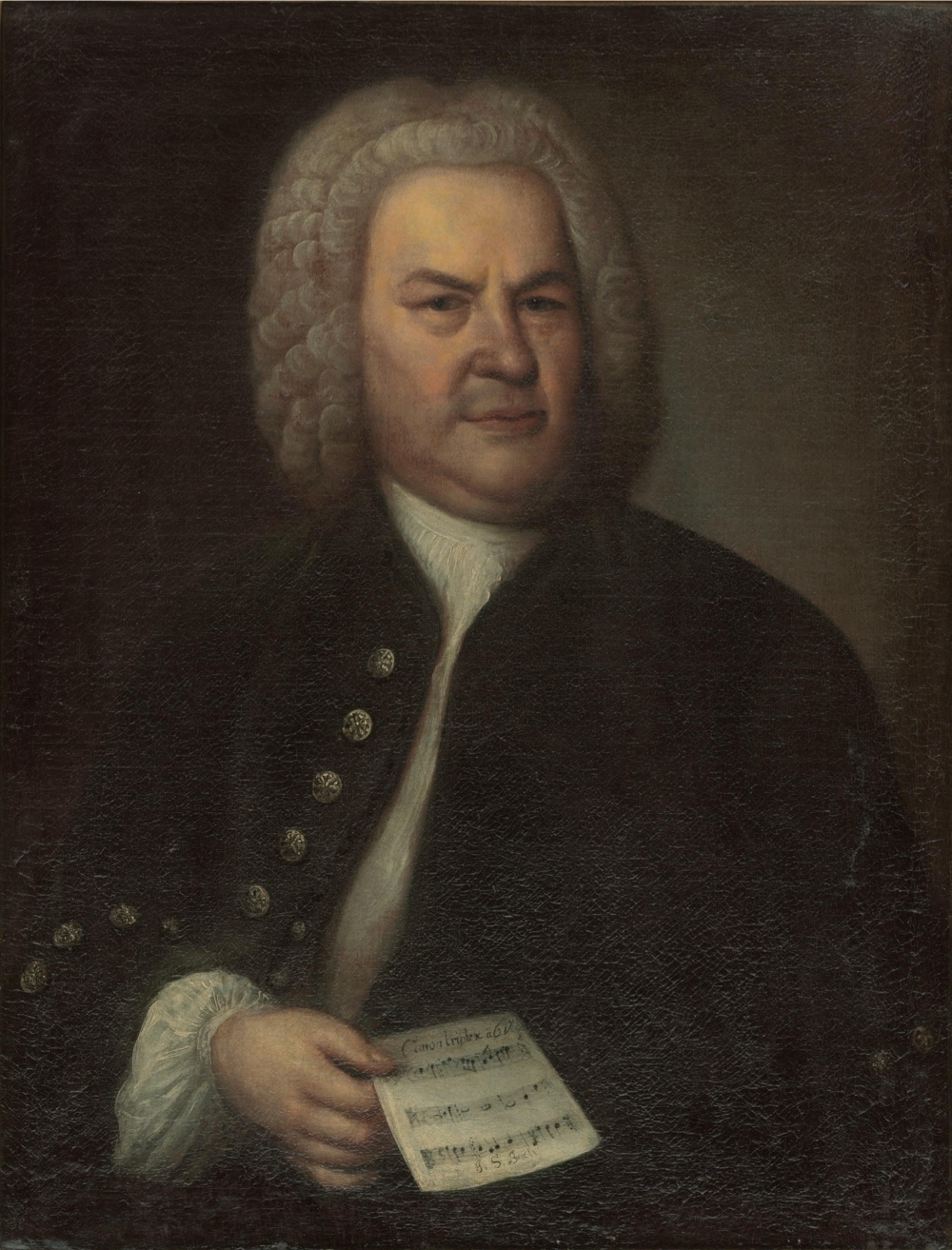

Johann Sebastian Bach by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (1746)

This is the portrait I was familiar with. It is housed in the council chamber of the Old Town Hall in Leipzig. It was given to one of Bach’s sons, Wilhelm Friedmann, when the Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences was dissolved in 1755. In the 19th century it ‘suffered’ more or less drastic restorations.

The portrait in the Bach Museum is a second version painted by Haussmann in 1748. It’s in much better condition.

Johann Sebastian Bach by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (1748)

It’s not clear what’s going on here. Maybe Bach wanted to replace the 1746 version he had given to the Society.

The 1748 portrait was bequeathed to the Bach Museum in 2014 by an American private donor who was a member of the Board of Trustees of the Leipzig Bach Archive Foundation.

After 265 years, the famous 1748 portrait of Bach by the Leipzig painter Elias Gottlob Haussmann has returned to Leipzig.

The portrait shows Johann Sebastian Bach in a formal pose at around 60 of age.

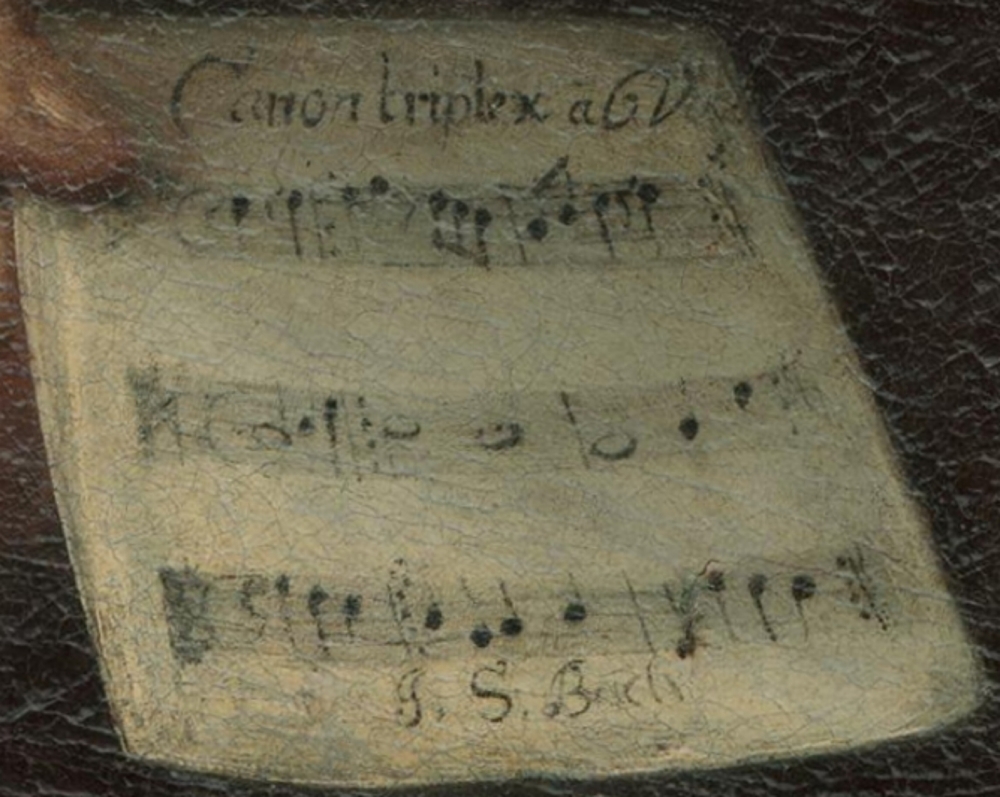

In his right hand, he holds a sheet bearing the Canon triplex à 6 Voc: per J. S. Bach as proof of the sophistication of his craftsmanship.

Haussmann painted two versions of the portrait. The second original, painted in 1748, is in a much better state of conservation. This is a captivating portrait, not only because of its glowing colours and sharp outlines, but also because of its moving history.

The 1748 portrait was part of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s share of his father’s inheritance and was once displayed as part of the voluminous collection of portraits belonging to Bach’s second-eldest son in Hamburg.

Read more about the history of this painting (scroll down to “Bach is coming home!”): New collectibles from our treasury.

Here are some more links I found interesting:

19th-Century Copies

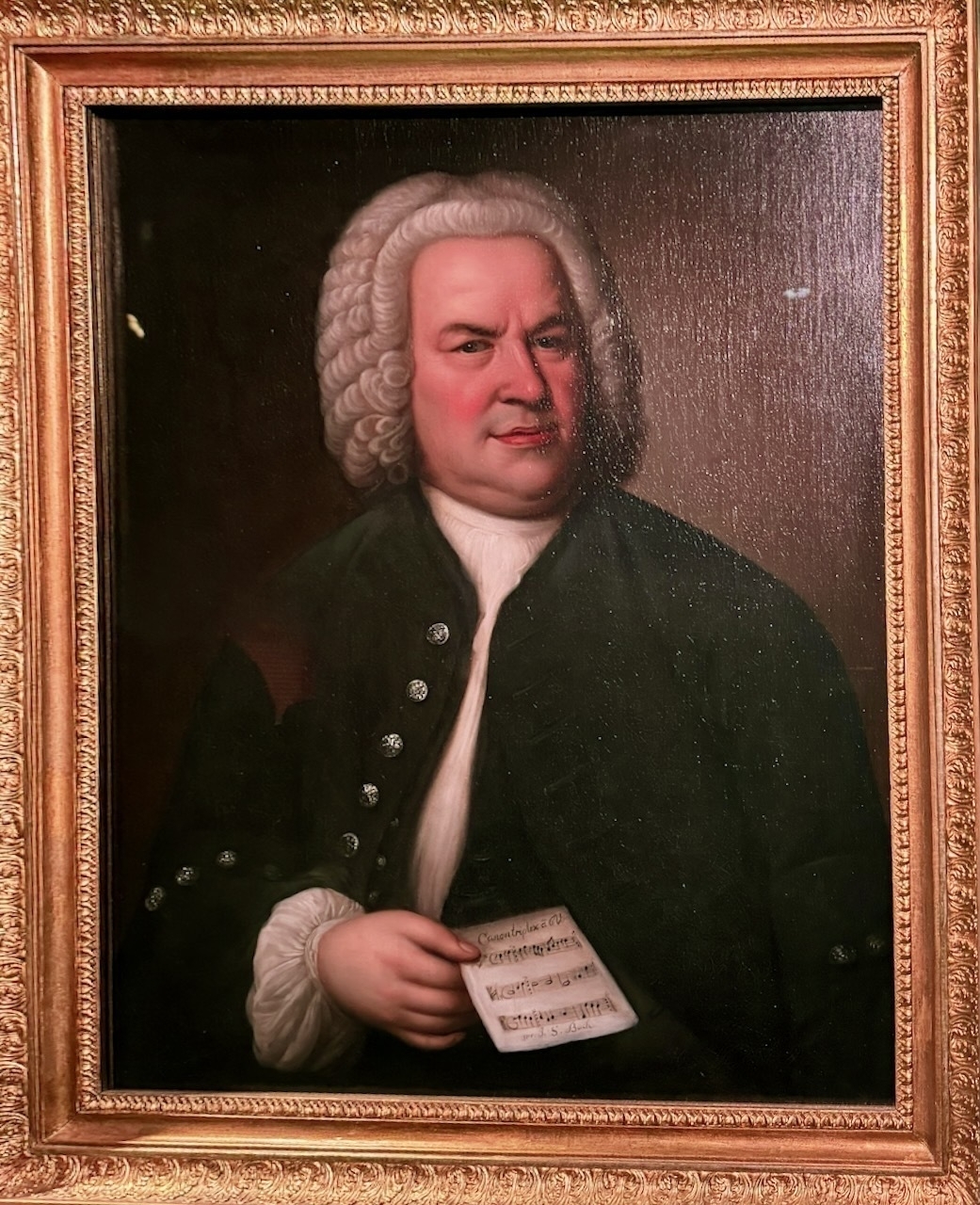

The Treasure Room also houses two 19th-century copies of the Haussmann portrait. They attest to the growing esteem in which Johann Sebastian was held after he was ‘rediscovered’ by Mendelssohn.

Copy by an unknown artist after Ellas Gottlob Haussmann, oil on canvas, mid-19th century

Copy by an unknown artist after Elias Gottlob Haussmann, oil on canvas, 1848

The copy shown here is known to have been commissioned by senior legal official Gotthilf Krüger from Halberstadt as a gift for his parents Gottfried and Auguste Krüger to mark their golden wedding.

Canon Triplex in 6 Voices (BWV 1076)

In the Haussmann portrait, Bach holds a sheet of music with the title: Canon triplex à 6 Voc: per J. S. Bach ‘as proof of the sophistication of his craftsmanship.’

JS Bach: Canon Triplex in 6 Voices (BWV 1076)

Detail from Haussmann’s portrait of Bach

The Grassi Museum uses the Canon Triplex in 6 Voices as part of it’s display on music engraving.

Here is the printed version from that display:

JS Bach: Canon Triplex in 6 Voices (BWV 1076)

Grassi Museum of Musical Instruments

Even though only 3 lines of music are notated, this is a complete piece for 6 parts or voices. It’s a type of ‘Riddle’ or ‘Puzzle’ canon that has to be ‘solved’ to be able to play it.

Here is the ‘solution’:

There are 3 groups of two voices. Each group is a canon.

The upper voice in each group is an inversion of the lower voice (it moves up when the lower voice moves down and vice versa). It starts 1 bar after the lower voice and is pitched either a 4th higher (upper two groups) or a 4th lower.

And the 3 groups work together to create one (short) piece of music. It’s also a perpetual canon (or round): there is no endpoint.

Have a listen. This performance starts with the lower group. The other groups join in turn. It’s like a very sophisticated ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat’.

As I said in the post about my visit to the Grassi Museum: this is geekery of the highest order. Bach loved and excelled at this stuff. What a perfect submission to the Society of Musical Sciences!

Here’s a link I found interesting: Maestro of more than music

Look beneath the surface of Bach’s music and you will find a fascinating hidden world of numerology and cunning craft.

🔥 This web page will blow your mind.

If you enjoyed reading about Bach’s Canon Triplex, you might also enjoy my post about another example of 18th-century geekery: The Gnomon of Saint-Sulpice.

Stay tuned for more adventures on our European Odyssey!